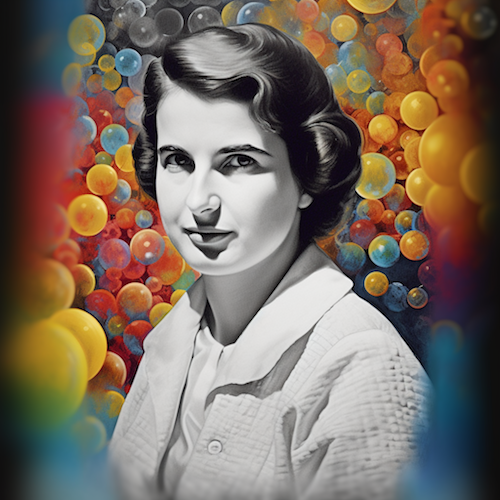

¶ Rosalind Franklin: The mother of DNA’s double helix

¶ Introduction

Rosalind Franklin (1920–1958) was a pioneering and brilliant chemist known for her significant contributions to the field of molecular biology. Her groundbreaking research on the structure of DNA, RNA, and viruses laid the foundation for modern understanding of the biological molecules that govern life's processes. She also did impactful research on coal and graphite that revolutionized several fields in industry. Despite her work, she was not awarded with a Nobel Prize. But three of her colleagues, who benefitted from her research, were.

¶ Early Life

Rosalind Elsie Franklin was born on July 25, 1920, in London, England. She was the second of five children born to a wealthy and influential Jewish family. Her father, Elias A. Franklin, was a merchant banker, and her mother, Muriel Franklin, was a homemaker. Franklin was a brilliant student from an early age, excelling in science and mathematics. She attended St. Paul's Girls' School and later studied at Newnham College, Cambridge, where she earned a degree in natural sciences. Her academic prowess was evident, and she went on to complete a Ph.D. in physical chemistry at the University of Cambridge in 1945.

¶ Rosalind Franklin’s main achievement

After graduation, she joined the Laboratoire Central des Services Chimiques de l'État in Paris, where she honed her expertise in X-ray crystallography, a technique crucial for understanding molecular structures. Her meticulous work led to a deeper understanding of coal and graphite's complex structures. She developed new methods for classifying coals and predicting their performance. Her work also helped to develop new technologies for using coal more efficiently, like, for example, the manufacturing of better gas masks used by the British in World War II.

Upon becoming a research associate at King's College London in 1951, Rosalind identified several crucial characteristics of DNA. She worked tirelessly in a hostile and sexist environment. With the help of an assistant, Raymond Goslind, she produced a photograph, known as Photo 51, the most famous X-ray image of DNA, that provided the first clear evidence of the double helical structure of DNA. These discoveries later played a fundamental role in accurately depicting DNA’s structure - one of the most important scientific discoveries in human history.

¶ How Rosalind Franklin’s work was stolen

While Rosalind was working on analyzing data from Photo 51, two other scientists, James Watson and Francis Crick, from Cambridge, were also working on figuring out DNA’s structure. They were shown Photo 51 by Maurice Wilkins, another scientist at King's College, without Rosalind’s permission. Wilkins and Rosalind had clashed before as he firmly believed that she had been hired to be his assistant - while she believed she was hired to do her own research. They had completely opposite personalities. Rosalind was strong and debateful. Wilkins was an introvert. Rosalind was isolated and downplayed by her male peers. But she kept working.

Using Franklin's photograph and extra data the duo had access to, again without Rosalind’s knowledge, Watson and Crick built a model of the DNA double helix. Franklin's data were crucial, but Watson and Crick did not credit her when they published their model in 1953 in Nature magazine.

Rosalind also submitted her work with the same conclusions of Watson and Crick’s. However her work was published after theirs in the magazine and taken as a confirmation rather than being acknowledged as the original work or an inspiration to their conclusions.

In 1962, Watson, Crick, and Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Rosalind was not, as she had died in 1958, and the Nobel Prize is not awarded posthumously. Moreover, the contributions of Franklin were not fully acknowledged during the Nobel Prize announcement.

¶ Next research

Considering the sexism and lack of support in King’s College, Rosalind transferred to Birkbeck College in 1953, where she did, again, pioneering work, this time on the molecular structures of viruses. In Birkbeck she found a welcoming and stimulating environment.

¶ Death

Only five years later, in 1958, Rosalind died of ovarian cancer at the age of 37. She was posthumously awarded the Royal Medal by the Royal Society in 1962.

¶ Legacy

Franklin's work has had a profound impact on our understanding of biology and medicine. Her discovery of the double helix structure of DNA has led to the development of new treatments for diseases such as cancer and HIV/AIDS. She is considered one of the most important scientists of the 20th century. Her team member Aaron Klug, from Birkbeck, continued her research, and won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1982.

In recognition of her groundbreaking contributions, awards, fellowships, and institutions have been established in Rosalind Franklin's name, dedicated to supporting women in science and promoting equality in the field. Her work remains an inspiration to those who seek to push the boundaries of scientific understanding and promote gender equality in all areas of life.

¶

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosalind_Franklin

https://ed.ted.com/lessons/rosalind-franklin-dna-s-unsung-hero-claudio-l-guerra